Political attitudes and beliefs have been shifting dramatically over the last few years. But, like the tides, they change direction relatively quickly. The pandemic seems to have curbed the attractiveness of ‘strong man’ leaders, but it’s also causing people to question the value of democracy.

A striking headline in today’s Times, declares “one in four French voters happy for the army to run the country”.

39 per cent of respondents say they would like to see at the head of the country “a strong man who does not have to worry about Parliament or the elections” – in other words a dictator – and 27 per cent a military junta.

These findings aren’t from a niche study with a small sample – it’s a very robust, nationally representative annual study of more than 10,000 people conducted by OpinionWay on behalf of Cevipof, the Centre for Political Research at Sciences Po, a leading university.

The French case is an up-to-the-minute example of a wider trend which sees core democratic beliefs under siege, particularly as a result of the way the COVID pandemic has been handled by governments across the world.

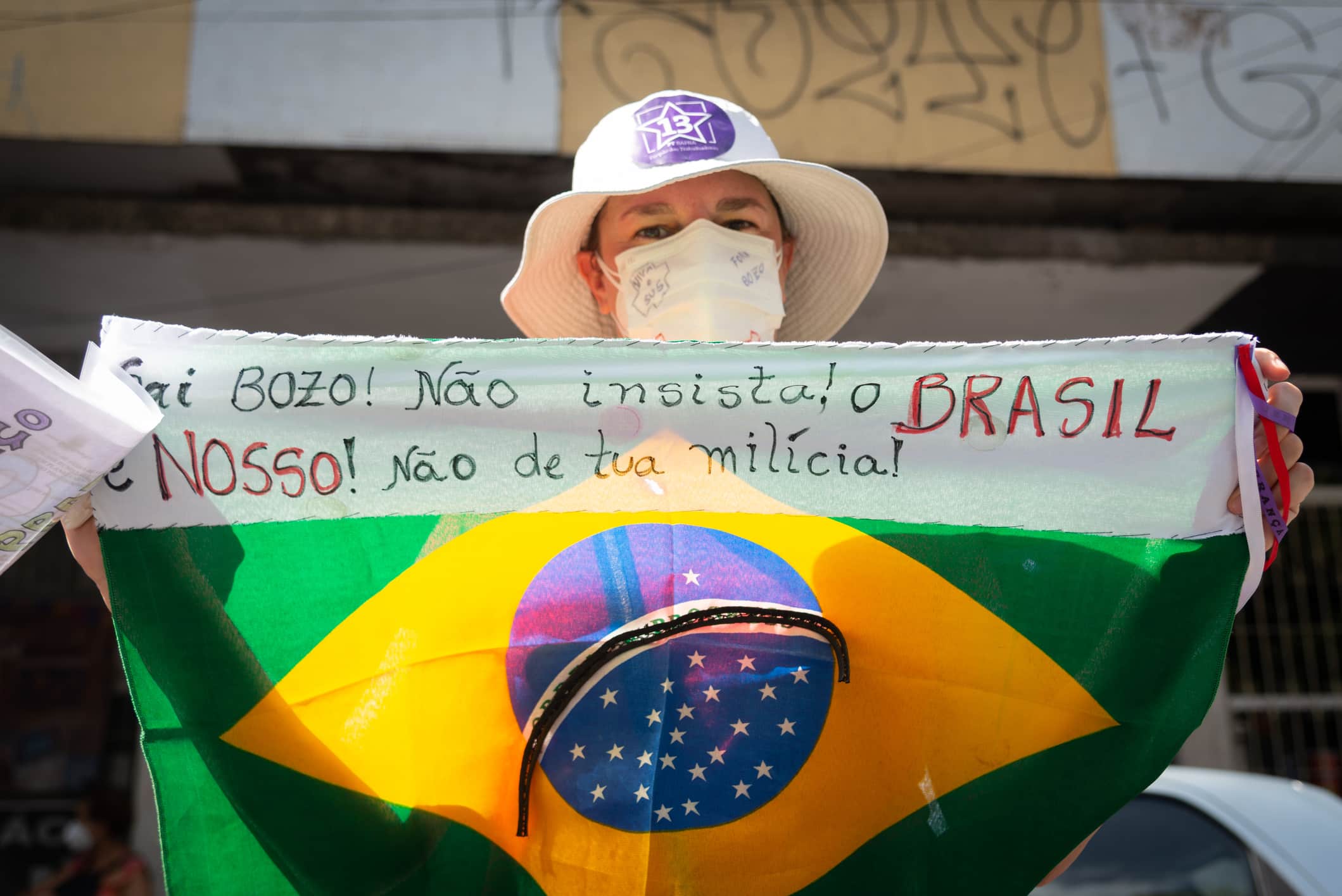

The response of Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro to the pandemic has caused a steep decline in his popularity.

Another study, called The Great Reset: Public Opinion, Populism and the Pandemic by the Centre for the Future of Democracy (CFD) at The University of Cambridge, has examined data from pollsters YouGov from 27 countries and 81,857 people from the last 18 months. They’ve then overlaid that with data compiled by the HUMAN Surveys project covering responses from 8 million people since 1958.

The report draws two conclusions, which could appear to be somewhat contradictory: “We find strong evidence that the pandemic has reversed the rise of populism, whether measured using support for populist parties, approval of populist leaders, or agreement with populist attitudes.

“However, we also find a disturbing erosion of support for core democratic beliefs and principles, including less liberal attitudes with respect to basic civil rights and liberties and weaker preference for democratic government.”

Dr Roberto Foa, Co-Director of the CFD and the report’s lead author explains more: “The story of politics in recent years has been the emergence of anti-establishment politicians who thrive on the growing distrust of experts. From Erdogan and Bolsonaro to the ‘strong men’ of Eastern Europe, the planet has experienced a wave of political populism. Covid-19 may have caused that wave to crest.”

“Electoral support for populist parties has collapsed around the world in a way we don’t see for more mainstream politicians. There is strong evidence that the pandemic has severely blunted the rise of populism,” said Foa.

France, the home of modern democracy, pictured on Bastille Day. A majority say they would now favour the country being run by unelected experts. Picture from Yiwen on Unsplash.

On average across the world, populist leaders saw a 10 percentage point drop in their favourability ratings between the spring of 2020 and the last quarter of 2021, while ratings for non-populists – on average – returned to around pre-pandemic levels.

Electoral support also plunged for their parties – seen most clearly in Europe, where the proportion of people intending to vote for a populist party fell by an average of 11 percentage points to 27 per cent.

In case you were wondering, Boris Johnson is not classed as a populist within the definition of the report.

You might expect a consequence of this to be a swing towards a greater appreciation for democracy and representative government.

However, the CFD study finds that the consequence of populist decline has not been a renewed faith in liberal democracy: in fact support has waned.

Citizens across the world increasingly favour technocratic sources of authority, such as having “non-political” experts take decisions. This is again borne out in today’s Cevipof study, which finds a majority of French people (52 per cent) would favour government by experts rather than democratically elected politicians.

Dr Foa explains: “Satisfaction with democracy has recovered only slightly since the post-war nadir of 2019, and is still well below the long-term average. Some of the biggest declines in democratic support during the pandemic were seen in Germany, Spain and Japan – nations with large elderly populations particularly vulnerable to the virus.”

In the US, the percentage of people who consider democracy a “bad” way to run the country more than doubled from 10.5% in late 2019 to 25.8% in late 2021.

Added Foa: “The pandemic has brought good and bad news for liberal democracy. On the upside, we see a decline in populism and a restoration of trust in government. On the downside, some illiberal attitudes are increasing, and satisfaction with democracy remains very low.”

With unrelenting pressure on Boris Johnson’s premiership in the UK, a French election just around the corner and a new US election, with the potential of another run by Donald Trump, just three years off, political soothsayers in major democracies across the world will be very focused on trying to interpret and adapt to these fundamental shifts.

One thing’s certain, however: we simply can’t accurately predict what other seismic events may come our way to cause the tide of opinion to change again.