The World Health Organization has certified China as malaria-free. Given that the country was reporting 30 million cases per year of the disease in the 1940s, it’s a major milestone in the worldwide campaign to eradicate the killer disease completely.

How has China done it?

Beginning in the 1950s, health authorities in China worked to locate and stop the spread of malaria by providing preventive antimalarial medicines for people at risk of the disease as well as treatment for those who had fallen ill. The country also made a major effort to reduce mosquito breeding grounds and stepped up the use of insecticide spraying in homes in some areas.

In 1967, the Chinese government launched the “523 Project”, a nation-wide research programme aimed at finding new treatments for malaria. This effort, involving more than 500 scientists from 60 institutions, led to the discovery in the 1970s of artemisinin – the core compound of artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs), the most effective antimalarial drugs available today.

“Over many decades, China’s ability to think outside the box served the country well in its own response to malaria, and also had a significant ripple effect globally,” notes Dr Pedro Alonso, Director of the WHO Global Malaria Programme. “The Government and its people were always searching for new and innovative ways to accelerate the pace of progress towards elimination.”

In the 1980s, China was one of the first countries in the world to extensively test the use of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) for the prevention of malaria, well before nets were recommended by WHO for malaria control. By 1988, more than 2.4 million nets had been distributed nation-wide. The use of such nets led to substantial reductions in malaria incidence in the areas where they were deployed.

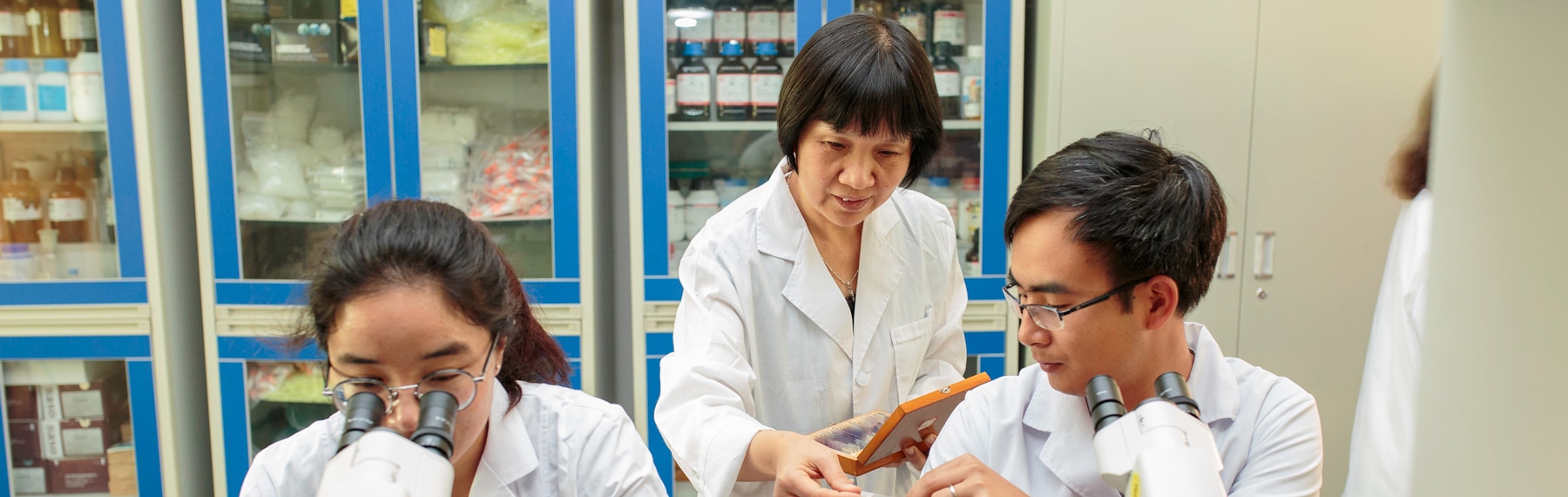

Dr. Dong Xueshu, a medical entomologist, examines one of the hundreds of species of mosquitoes he has identified in Yunnan Province. Yunnan Institute for Parasitic Diseases, Pu’er Simao, Yunnan.

By the end of 1990, the number of malaria cases in China had plummeted to 117 000, and deaths were reduced by 95%. With support from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, beginning in 2003, China stepped up training, staffing, laboratory equipment, medicines and mosquito control, an effort that led to a further reduction in cases; within 10 years, the number of cases had fallen to about 5,000 annually.

In 2020, after reporting four consecutive years of zero indigenous cases, China applied for an official WHO certification of malaria elimination. Members of the independent Malaria Elimination Certification Panel travelled to China in May 2021 to verify the country’s malaria-free status as well as its programme to prevent re-establishment of the disease.

Subscribe

Sign-up to receive our newsletter

Why did it work?

China provides a basic public health service package for its residents free of charge. As part of this package, all people in China have access to affordable services for the diagnosis and treatment of malaria, regardless of legal or financial status.

Effective multi-sector collaboration was also key to success. In 2010, 13 ministries in China – including those representing health, education, finance, research and science, development, public security, the army, police, commerce, industry, information technology, media and tourism – joined forces to end malaria nationwide.

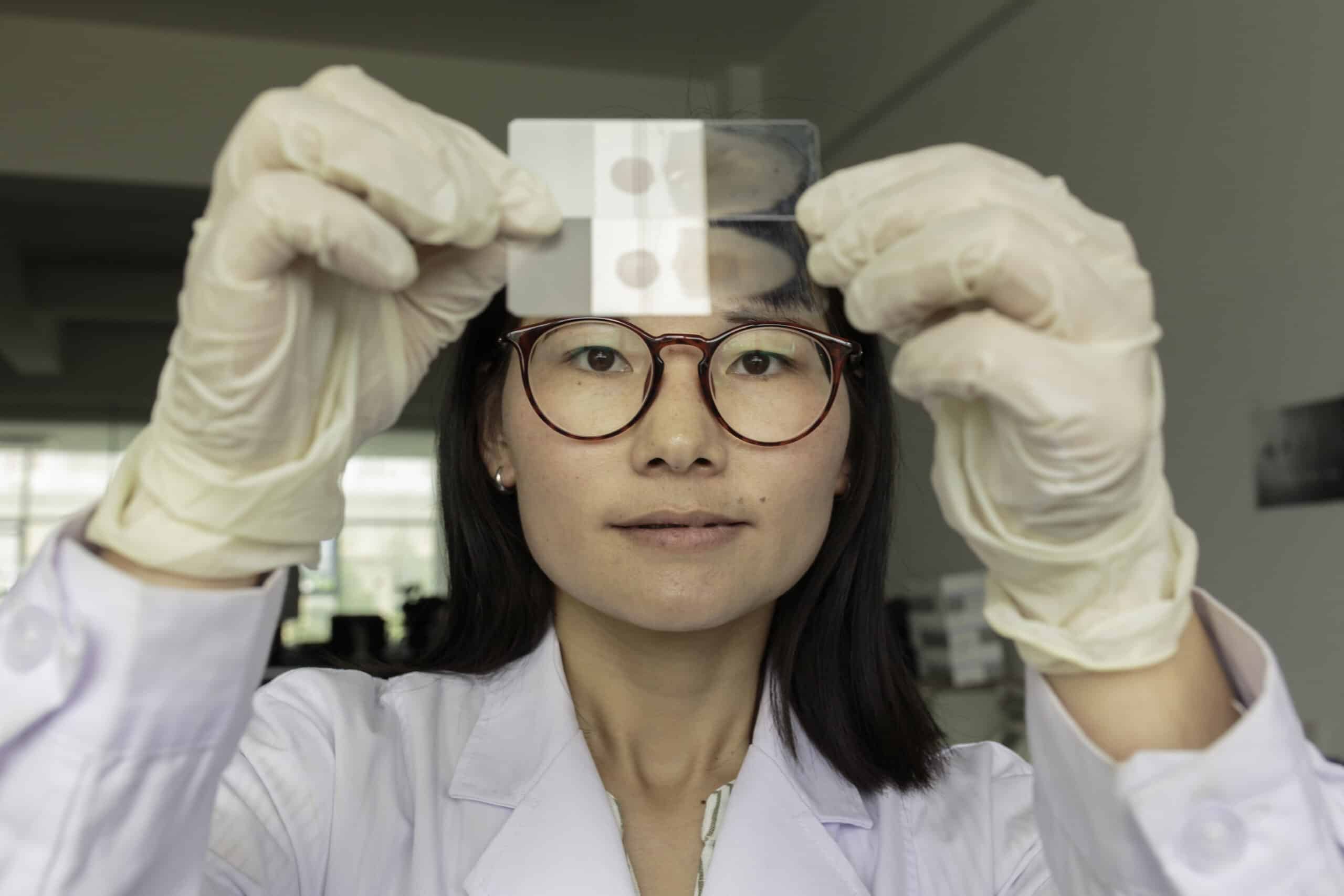

In recent years, the country further reduced its malaria caseload through a strict adherence to the timelines of the “1-3-7” strategy. The “1” signifies the one-day deadline for health facilities to report a malaria diagnosis; by the end of day 3, health authorities are required to confirm a case and determine the risk of spread; and, within 7 days, appropriate measures must be taken to prevent further spread of the disease.

Nan Laodi, from Myanmar, and Huang Pei Pei, a Chinese student, use bed nets every night in their dorm room at the Friendship Primary School in Daluo, which is a few hundred metres from the Myanmar border. Meng Hai County, Yunnan Province. April 2019.

Keeping malaria at bay

The risk of imported cases of malaria remains a key concern, particularly in southern Yunnan Province, which borders 3 malaria-endemic countries: Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Myanmar and Viet Nam. China also faces the challenge of imported cases among Chinese nationals returning from sub-Saharan Africa and other malaria-endemic regions.

To prevent re-establishment of the disease, the country has stepped up its malaria surveillance in at-risk zones and has engaged actively in regional malaria control initiatives. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, China has maintained training for health providers through an online platform and held virtual meetings for the exchange of information on malaria case investigations, among other topics.

Xu Yanchun, a laboratory specialist, holds blood smears that she will examine for malaria parasites. Rapid diagnosis of malaria is a key aspect of the “1-3-7” strategy. Yunnan Institute for Parasitic Diseases, Pu’er Simao, Yunnan. April 2019.

Malaria in the rest of the world

Despite the positive news from China, malaria is rife elsewhere. In 2019, there were an estimated 229 million cases of malaria worldwide with an estimated 409,000 deaths in that year. Children aged under five years are the most vulnerable group affected by malaria, accounting for 274 000 (67 per cent) of those deaths. Africa suffers disproportionately with 94 per cent of malaria cases and deaths.

The fight against the disease continues with total funding for malaria control and elimination reaching an estimated US$ 3 billion in 2019. Contributions from governments of endemic countries amounted to US$ 900 million, representing 31 per cent of total funding. Major NGOs and philanthropists are also playing a major role, with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation contributing over US$ 200 million per year.